A recent PBS program on the American efforts to save art and architectural treasures during WWII featured my father's 319th bomber group. They had been chosen to bomb the marshalling train yards in Florence, because they were the best bomber group in WWII, and they carried out a precision bomb run dropping all their bombs on a thousand by three hundred foot space, sparing Florence's priceless buildings and treasures. They received a Presidential commendation, for this bombing raid and for another on Rome.

Fellow pilots used to say that my father was the best pilot they had ever seen, drunk or sober. He was modest, and lucky, because he flew many dangerous missions. He lost a lot of friends. He told me that the book Catch 22 was based on the experiences of his group - he knew the people described in it. Enough said. Read on…

My father stopped flying combat missions on October 19 1944… maybe this is the explanation.

Sitting Ducks or the milk run

©Patrick McDonnell 2019 - 2021

The definition of a milk run is slang for a routine mission that has a low chance of danger.

My father’s final WWII combat mission has always been a mystery to me. He never talked about it. Only after years of research did I find out why.

My father was a man of many mysteries.

For years he would come visit us. Then he would go off by himself. At first I wondered if he was up to his old habits of bar flying. Finally, I found out what he was up to – he was dancing. Eventually he invited us along. I remember his fancy outfit; a hand painted tie, white belt, and patent leather brogues. It was wonderful to see him ‘cut a rug’ on the dance floor. His face lit up. His age melted away. He was a young man again. My youthful memories of him was of a ghostly figure who smelled of camphor and booze. After the war he stayed in the military to continue flying. I hardly saw him.

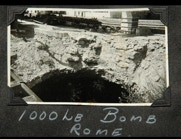

The war changed him. He wanted so much to serve in the military. So he had surgery to correct a deviated septum in his nose before he enlisted. He entered officer training school, pilot training, and finally qualified to be a pilot in B-26 bombers. Just before shipping off to North Africa he married. Ever the optimist, he believed he would return alive. Full of enthusiasm when he arrived in North Africa - where the bomber group’s planes hadn’t arrived - he jumped into an idle fighter to fly off searching for the enemy. His wartime photo albums attest to years of combat with faded pictures of exotic places, fellow pilots, favorite bombers, and bombing runs. Here and there are inklings of the truth. A curly edged photo shows a crater in a Roman train station made by a 1000-pound bomb. His pictures show him changing. Malaria made his teeth fall out. His leather flight jacket was adorned with a growing numbers of missions represented by bomb icons. I proudly displayed his unit patch of the 440 squadron of the 319th bomber group. Somewhere I still have the jacket with that patch of a cartoon bunny dropping a bomb – their unit icon. At the end of the war he looked as worn out as the jacket; his face was creased and he had the thousand yard stare.

When I was twenty he saw me reading Joseph Heller’s anti war novel Catch-22. He told me he knew all the people in the book. The naked man in the tree. The morphine that had been replaced by water and the men who refused to fly. I didn’t believe him. I should have. To make things worse, my mother used to tell to me, “If your father hadn’t refused to fly in the war, he would have ended up a general.” What was the truth?

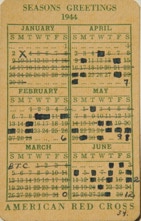

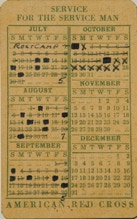

I came across the yellowed Red Cross calendar card he kept on him for the year 1944. It was like the Rosetta stone of his war time experiences. To find out more I went to the aviation museum in Washington D.C. and purchased a book covering the years he flew B-26s in the Mediterranean Field of Operations. Only then did I begin to understand. In that book I found a quote from the 319 bomber group’s flight surgeon, Dr. David O. Gorlin, who said, “We have a new 40-mission system. After 40 missions the flight surgeon automatically becomes a son-of-a-bitch.” Because experienced pilots and crews were in short supply, the number of missions required to fly before crews were allowed to return home was raised again and again; 40…50…60… In the winter of 1943-1944, the enemy was loosing, but not defeated. Joseph Heller invented the phrase ‘Catch-22’ to explain the paradox of the situation; if you were sane enough to refuse to fly, you were sane enough to fly.

October 19th 1944 was not a milk run for my father.

In the declassified records of his unit I learned what had happened. The blackened out dates on his 1944 calendar represented combat missions. Up to October of the year he had flown 53 combat missions. That didn’t take into account his combat missions of the previous year. After the 19th it showed zero combat missions. Something important had transpired.What?

Shakespeare wrote that brave men only die once. Some don’t have that option. Before the D-day landings in Normandy, fierce battles were waged around the Mediterranean as Allied forces fought bravely. A long bloody campaign started in North Africa, continued up into Italy and then into Southern France. After months of fighting, enemy aircraft had been chased from the sky. Combat missions for bombers became ‘almost’ like milk runs. A fatal decision was made. Because few if any enemy fighters had been seen in the first eight months of 1944, the B-26 bombers were stripped of some defensive weapons to give them more range and to carry more bombs.

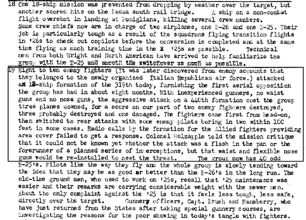

On October 19th, my father was a pilot in one of the 20 planes in the 440thsquadron of the 319thBomber Group flying on a mission to bomb the railroad bridge at Mantua. They were jumped by ten enemy fighters. To quote the mission report, “With inexperienced gunners, no waist guns and no nose guns, the aggressive attack on the 440th formation cost the group three planes down…the fighters came first from heads-on, then switched to rear attacks with some enemy pilots boring (in) to within 100 feet in some cases. Radio calls (for help)...failed to get any response.”

I can only imagine in a small way what that must have been like. A fragile craft, made of thin aluminum and Plexiglass, was crewed by men who knew death could come from any quarter and yet they persevered. Anti aircraft guns shot shells exploded in angry black flack bursts, the shrapnel hitting the plane. A piece could wound or kill the crew and pilots. Suddenly killing machines came at you shooting and you were a sitting duck. My father’s calendar card was empty of missions from that day on. At the end of his tour of duty he was assigned to the training of pilots. After the war, he re-enlisted to fly again. It was what he did best.

When my father passed away in Florida, his heart surgeon came to the funeral home with his kids to pay their respects. They had become good friends. The surgeon told me my dad never mentioned the war though he did say my dad was a tough guy to kill. My father liked to fly, when he retired he took up dancing. Flying must be like dancing. Only at low altitude.

In a newspaper article, written during the war, it quotes him as saying that flying in combat was ‘unexciting’, and that his plane often returned to base from a mission looking ‘like a sieve’ from enemy fire. Like many veterans both censorship and a need to forget made them taciturn. My father’s generation was not interested in self promotion, nor fame. He never mentioned the bombing raid on the Rome’s Ostiense and Florence main railroad yards on March 3rd and 11th that spared world heritage architecture and artwork. My father’s unit - the 319th- was one of the bomber groups chosen because they had a reputation for accuracy. They received two presidential citations for their ‘brilliant accuracy’. That accuracy came at a great cost, it was the fruit of incredible ability and bravery, obtained after hours of flying combat missions over two years. He told me, “We did a steep dive in formation as we approached the target so the enemy’s AA guns couldn’t judge our altitude. We leveled out for the bomb run. Then we flew like hell out of there.”

The mysteries my father kept about dancing and his war record were linked, he was accomplished at both. I recall fondly my son and his wife dancing at their wedding. They went to Italy on their honeymoon. That would have pleased my father. Somewhere his spirit is still flying and dancing.