A bike trip in Erie 1972

©Patrick McDonnell 2000-2021

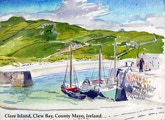

Watercolour by Patrick McDonnell

There is an old Irish saying, "may the road rise to meet you and may you always have the wind at your back." When you bicycle Ireland, you wish it was always true. But it never is, hard as you may try, Murphy throws a monkey wrench into life. So either you accept the inevitable, or you fight and get blown away, there are not two ways about it. As my Irish grandmother used to say. ’Tis a hard ting, life, but it is all we have so we must make the best of it.’

The Irish are a strange people, part storytellers, romantic, always heroic and certainly never dry. Having grown up with a father who kept faith with his culture, I knew both the good and bad sides of them. But the truth is never clear and precise to the Irish, or to anyone for the matter. Only by going to the root, to the old country, can you discover the truth. So after living in Paris as a student for a year, I decided that I wanted to find my ancestors. Not an easy task, as Murphy's law will confirm.

After buying my Aer Lingus ticket, from the beautiful lassies at the Irish Tourist Board (I remember you all so fondly, thank you for taking the time to talk to a lonely student), I looked forward to leaving for Ireland. An extra bonus was the weather had turned mild and sunny for a week in Ireland. There are hundreds of Irish photographers who sit for days, sometimes months on end, with cameras filled with film, waiting for that break in the clouds, that once in a blue moon weather phenomena called "sunshine". When it happens, they all rush out and take thousands of pictures which they immediately proffer to the Irish Tourist Board to be published in brochures. The reality in Ireland is quite different. Wet!

My Odyssey started and stopped at the Aer Lingus check in counter when they found out my passport was expired. Not a good thing, but usually over looked, however events in Ireland - as they will always do - had forced the police to be more vigilant. They were not going to let in a long haired student into their country, especially as the British had just found out that the Irish were using nitrate fertilizer for something other than farming.

Ah, yes. The English finally noticed that the Irish, who produce enormous amounts of Bull shit, were importing amazing quantities of nitrates for their fields. Some brilliant British customs officer had suddenly realized - remembering his high school chemistry - that nitrate can easily converted into nitro glycerine and combined with other sundry chemicals can be turned into TNT and plastic bombs. So my trip to sunny Ireland was curtailed while I applied for a new passport. (The female photographer loved my long tresses; falling to my shoulders.)

Not to worry, my friends the Ms took pity on my and I languished in luxury at their 16th arrondisment apartment, in rooms the size of basket ball courts, above the Israeli Ambassador's apartment; heavily guarded. The Ms had just lost their father to cancer and were happy to see me. I was a good friend of the son, and we all had a good time during that week together. Meanwhile, the Irish girls at the ticket agency, knowing how I longed to go to Ireland, said "fine, not to worry, we will get you another ticket a week later." One of them took my ticket and had a glorious time.

A lot can happen in a week. I flew off to Ireland, finally. My days of frustration turned to joy as I flew into Dublin. You have to understand that Ireland is called the Emerald Isle for good reason; it has every shade of green possible. Different from England, which is also green but whose country side is preserved as a game reserve for the rich, with forests and lanes buried into the ground. Ireland was and is the bread basket of Great Britain. Ireland is farmland. The soil is rich; all those nitrates! All the Irish bullshit!

I arrive in Dublin, fair city, small back water place really. and I have an introduction to a friend of a friend. A Jewish photographer off of O'Connell street. He invites me home, to a dinner where his wife falls asleep during the meal, and his modern son in law talks of his new "Caravan" with his goy wife. The photographer tells me that the Irish are the salt of the earth; glad not to be a Protestant.

The play boy of the Western World arrives

I jumped on a train to the West as soon as possible. In Sligo, I rented a three speed bike and armed with my military maps, I cycled into the country. The first day, as I passed Ben Bullen, I visited Yate"s grave site and continued up the coast, the weather turned from sunny to gray. A harbinger of things to come. That night I stayed in the hamlet of Easky in a Bed and Breakfast, taking High Tea with a French couple. He was there to fish for Salmon, the best in the world. I also saw people who were traveling in Caravans, not Tinkers, but tourists playing Tinker. (Tinker's are Irish Gypsies, or "Travelers")

Irish High tea. What a wonderful thing that is. Tea with crumpets and Irish Soda bread like my grandmother used to make with cucumber sandwiches and tomato sandwiches on white thin sliced bread. Oh heaven could not be far away, the angels must be Irish, and speak Gaelic. The bed had Irish linen on it, crisp and soft, fresh smelling from drying out in the salt breezes. After tea, I walked around to sketch the fishermen in the creek that flowed into the fog shrouded ocean. The donkeys and sea birds eying me with disdain, or curiosity. An "Irish mist" fell as I made my way back to the warm lights of the village and to a much deserved rest.

The weather worsened becoming colder and wetter each day. I came to understand the Irish stubbornness, as I struggled up and down wet

mountain roads, building up my muscles and fortitude. I discovered that the Irish do not give up, even when they are given nothing but stone fields to plow and grass to eat. Eventually they emigrate, witnessed by all the empty houses, but they never forget. Emigration is not a failure but a turning of energies to new horizons. The Irish are used to hardship. They make light of it, laughing, singing and drinking.

The Troubles begin

Two events were taking place that summer in Ireland which would add to the weaving of its history. The vote to join the Common Market was soon to take place and the "troubles" had begun in Northern Ireland resulting in the arrival of the British Army. Despite the uproar, the violence and political upheavals, the Republic of Ireland was calm. Deceptively so. The country side and the country is a study in contrasts. A place, like Rouses Point near Sligo, is beautiful and peaceful beach on a sunny day. Then you find out that the day before, in a storm three men had drowned. The county echoes the Irish character; they are a peaceful kind, generous and loving people capable of killing you with a smile; blowing you to smithereens or "knee capping" you if you cross them. They will be sad about it later and sing a song about it.

You can never escape from history in Ireland, it takes on a new meaning there. The truth, already meager in History Books, becomes embroidered and distorted even more as the tales are retold and the songs are sung in the Irish pubs. The pubs segregated the women and the men. As a Yank seeking his ancestors I was fair game for the tale weavers. My name was suspect for many reasons. "Scottish are you?" was the question I was asked many times, "Protestant, are you?" "No, not for many generations; if ever" I would reply, my family was Gallowglass free-lance warriors. Or were they a deformation of O Donnell or whatever. The truth is never clear in Ireland, if anywhere.

I would tell them, " My grandfather was run out by the black and tans". And they would nod their heads wisely and say, "Eye, the McDonnells were a bothersome lot, they were always getting into trouble." And what of my Grandmother's people, the Lavelles, the French evident in their names? They were still around, owning half of Achill Island. The Napoleonic Invasion had left them high and dry. Like the previous Spanish Armada which had washed men up on the Western shores, an Irish woman never lets a good man go to waste. So I found my ancestor's descendants, this strange race of men and women hanging on to the West coast, hanging onto the worst land except for, God help you, north of Connemara with its fields of stone. (Genetic testing has found the Western Irish can trace their roots to Spain, and the Basque, another race of people who lack indo-european language roots, maybe Minoan?)

County Mayo

Mayo, "Oh, my God," stuck out at the Western end of the island, the last place you would see before you left to go to America. I biked it. The long and short of it. County Mayo became my bane and my brother, my muscles bulged, my Sartorious muscles came alive, and my thighs turned sinewy. To this day, I look down at them, my Irish Quadriceps, and I think of the miles of lonely road I traveled. One day, I went 100 miles without seeing a soul. Except a dog in the middle of the road. There were days when I was wet, drenched to the skin, my muscles screaming with the cold and pain of digging in as I climbed along side a cliff, the noise of the ocean filling my ears. On Achill Island, there is a hair pin turn, just before the beach, where I almost went over in the ocean. In the pub, they tell of a drunk driver who did, his car sandwiched into the beach bellow. They had a wake for the car.

I stayed in Youth Hostels, some plush, some hovels only heated with peat. When I could find one, or felt the need for a hot bath, I would pay a pound to stay in a B and B. At the Currane hostel, a priest and a young couple arrived in a hustle, the black frocked priest playing the fiddle like the devil himself, the couple singing and dancing in front of the peat fire. They passed the hat around to the astonished students, making a few bob and were gone into the night like a flash. Were they real? An Irish apparition.

Dreams are like that, afterwards, you wonder if it really happened. My dreams were filled with thoughts of women as I slept amongst men, in the dormitory. There was a dearth of women, in fact in the farthest reaches of county Mayo, I witnessed the women travelers staying at the hostel who went to the local pub and attracted such an admiring crowd that the Hostel owner had to stand guard at the door all night to keep the Irish bachelors at bay. Ten men to every woman in the Irish countryside, the reverse being true in Dublin. Desperate dreamers, lonely hearts! The women were not tied to the land, did not want drudgery. The English laws of first born inheritance had not been applied to Ireland, every one of the Irish brood inherited the land, so it was cut into smaller and smaller parcels. Forcing the immigration of the others. The women soon followed, not wanting their mother's life.

The way it used to be

Ireland is a land of hope and youth. Ireland is Catholic and banned contraceptives and abortions(in the 1970's). So children are everywhere, fresh, freckled and red headed. Friendly, open, full of questions and not afraid of strangers. In one village, the only crime was that a bike had been stolen by a foreign student. Call the Gardia! Never heard of the like before. This is Ireland where no one locks their doors, they are poor and trusting, there is nothing to steal, and if you wanted it they would give it too you. I remember many a time stopping my bike on the road beside a house in the middle of no where, and suddenly a woman runs out to me to offer me milk. If they have no milk, they would offer me water. Irish hospitality!

Nowadays, I doubt that would happen in Ireland. Too much money, too many tourists have come to spoil its openness and cleanness. Innocence can only last while money is not involved. Once the rich arrive, with their travelers checks and hard cunning to cut you down, the natives grow up, grow wiser. Fortunately, I saw Ireland before the European Common Market poured millions in to replace the thatch roofs with slate. Still, the innocence subsists in the Irish, the sweet callowness of the race flows underground, hidden from the casual traveler. I saw the spring from where it flowed. Just like seeing seedlings before they grow into a forest.

I visited Westport and Newport, the towns where my grand father and mother came from. I visited Westport House and met the lord; a friendly Anglo Irish who everyone loved (years later I found out why. His ancestor went into bankruptcy to house and feed his tenants during "The Great Famine ".) I watched the British troops move into Londonderry on TV, watched firebombs and hate unfold in the North. Then I biked to Croagh Patrick, 50 miles, climbed it's 2,510 feet height with other pilgrims - but not on my knees- and spent a cold night on top , waiting for the dawn to break. With a German student, who had swam the Elb river to escape East Germany, we

climbed down again, and slept in a barn. Exhausted, but full of youthful vigor, I biked back 50 miles to Newport to sleep all day.

The next day I found my German friend at a Youth hostel, and with a French student we hired a Curragh, and rowed to a deserted island. The ocean was calm, thank God, because we knew nothing of rowing in this cork like boat that bobbed about like a wild horse. In rough weather it must be impossible to steer, but the Irish fisherman could do it. The water was clear as green glass, transparent as the Mediterranean, colder. The island held nothing but goats, black faced and vocal. The houses were abandoned yet for three young men in a boat, we felt like Robinson Crusoes seeking adventure and women, finding neither, not that it mattered. Where were the women?

The women I met were married, in religious orders, or were not interested. ( Even the female sheep started to look good to me.) So I lived like a monk, everyday, a new hill and vista to see and conquer. I talked to a few people or I spent silent hours on my bike stopping to draw or take photos. Both things were rich and comforting. The Irish would speak in melodious tones. A mystery, until I heard Gaelic spoken for the first time and understood it is the language of birds. Like in the book " Green Mansions ". The land spoke to me with its beauty; its winds and waves, its greenness and rocky desolation.

I took the mail boat to Clare Island in Clew bay, no cars allowed. I saw my first and only black man in Ireland; he stood out like a sore thumb. I remember my Irish grandmother talking about arriving in America and saying how she had seen all those dark men. She a Black Irish women! When I asked what it meant, to be Black Irish, I never received a decent reply. Was it the hair, dark and swarthy, as opposed to the Celtic red hair? Was it the Jewish, Spanish, French genetic contributions? Was it the remains of the original Irish, the race of little people who lived in Ireland before the Norman, Celtic, Anglo Saxon invasions? The Irish are supposed to descendants from the Minoan races. Even the Phoenician voyagers spoke of the land at the ends of the earth; of the dark people who lived there.

A Grain of Truth

One incident stands out in my mind. At one of the youth hostels, I had a conversation with two other cyclists. One Irish and one Dutch.

The Dutchman was bragging about how Holland was the best place to bike because it was flat. The Irish student made a comment I will never forget. He said, "if you always cycle on a flat you will never know the glory of climbing for hours up a hill, or mountain and then coasting down the other side for miles. What a glorious feeling you miss in a flat country."

I never understood until later in life what he meant. In your life, if nothing happens, if you always have the same friends, do the same job, do the same humdrum things you will have a safe and boring life. But if you dare, if you are willing to suffer, if you try to climb the heights, to do better, to study and try hard if not impossible tasks, then you will be rewarded - how ever briefly - by the joy of that down hill run. The exhilaration of success may be brief, your happiness may not last. You may even fail; crash and burn. But better that than mediocrity and boredom.

I fell ill at one point, sick of the rain and cold, and I stayed in the luxury of B and B's in a warm bed after a huge warm bath. One pound per night. I was bitten by a spider, developed an allergic reaction, and took a Benadryl tablet to over come the effects; my head spun, I felt dizzy on my bike, as if I had drunk some Pocheen, an illegal beverage. I stayed in bed and rested, saving my forces.

I remember the children of Ireland, the tow headed ones, the red heads, the freckles. The richness of Ireland is it's children, a treasure which finally bore fruit years later in the Irish economic miracle. Still there are other visions, other images that stick to my mind. The black faced sheep. The kindness of the Irish, the first bitter taste of Guinness. The dog sleeping in the middle of the road. Elbows bent at male only pubs. The Irish wit, and witticism.

Sligo town

When I returned to Sligo, under Ben Bullum, muscles bulging, sun tanned and wind weathered face, I met three Irish girls who were at the bike rental / tourist office. I arrived in Sligo with more muscles than when I left. The hills that seemed enormous leaving Sligo, were nothing to me now; they were mohills. I must have looked like a sight. Steam boiling from me, my body like a furnace after riding for a week. My body hard as rock. For all that I stood shy and tall, dark and handsome. I was not aware how alluring I was to females, I had only seen female goats and sheep for a week.

The girls eyed me with interest bordering on lust. I was weary, wet and had not had a woman in weeks. They must have sensed it. They were twittering and jostling each other, looking at me as if I was a prize bull Just by luck, they said there was room at the B and B they were staying at. I was put in a room next to them.

They offered to show me around town. An offer I could hardly refuse. So off we went, hitchhiking, walking and talking. One was blond, one was brunette and one was auburn; they all were fascinated by me, as if I a was an alien who had landed from a UFO. They wanted to show me Yeat's country, all the places he wrote about. Inneshfree, Ben Bullen, Rosse's Point. They twittered to each other in Irish, smiling, laughing and making me feel very shy and masculine.

They showed me Rosses Point, Inneshfree, the place where the swans swam, all places evoked by Yeat's poetry. We returned to their room, where they continued my Irish education.

All things come to those who wait.

We traveled back to Dublin together and there I had more adventures. But that is another story altogether.

©Patrick McDonnell 2021